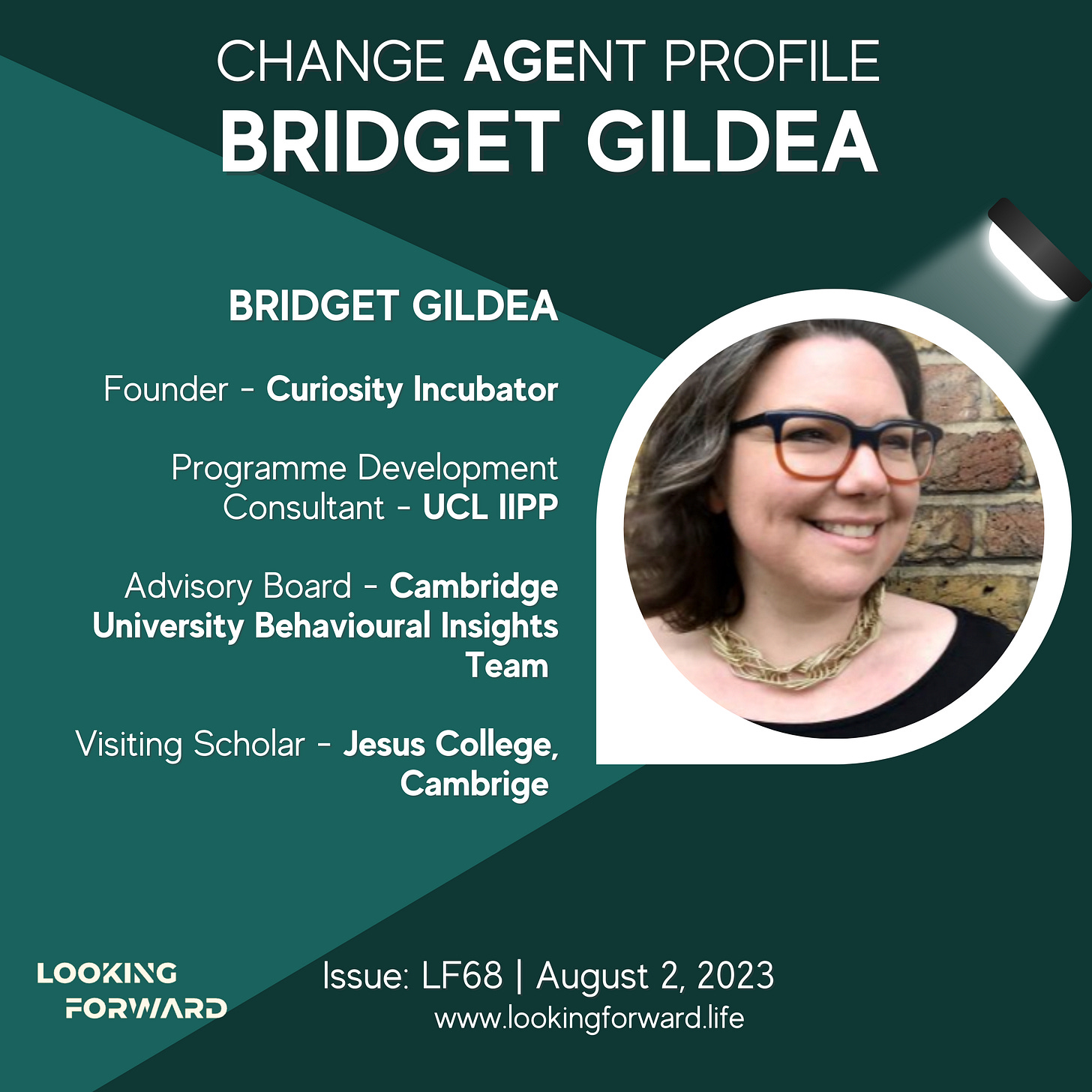

Change AGEnt Profile: Bridget Gildea

LF68 | Profile of Bridget Gildea who spends her time working on applied behavior change with a focus on mission-driven innovation and impact.

Bridget Gildea lives and breathes behavior change and applied learning; having studied and worked with some of the pioneering thinkers and research organizations in the area.

A Brit, she worked in the US, founding the first in the world practitioner programme on Behavioural Science with leading faculty at Harvard’s Kennedy School, and now splits time between building applied practitioner programs for IIPP at UCL (led by the inimitable Mariana Mazzucato), and running the ‘Curiosity Incubator’ at Jesus College, Cambridge (incidentally, my alma mater).

I spoke to her about the fast-moving landscape of behavior change and her efforts to scale up such efforts, working at UCL and Cambridge University. I used the well-known behaviour change model - EAST - to frame a number of her insights and anecdotes.

Creating mission-driven practitioner programs at UCL

Mariana Mazzucato is well known for pioneering mission-driven innovation, and giving the public sector a more central role in innovation than merely de-risking private sector innovation and fixing market failures. UCL is looking to build out new programmes beyond PhDs and MPAs, to bring these insights and approaches to scale.

Terminology is tricky here (don’t call it ‘exec ed’...). Bridget points out that the quicker we move from didactic learning (lectures and powerpoint) to applied learning when dealing with expert cohorts, the better, and that’s a big focus on the programs she’s building with the team at IIPP. One aspect she’s focused on now is integrating feedback loops into learning programmes creation, getting feedback from peers, mimicking on-the-job application of core concepts to support the sharing of IIPP’s innovative thinking.

Upskilling innovators and proving impact with the ‘Curiosity Incubator’

Bridget’s passion project is running the new Curiosity Incubator at Jesus College, Cambridge’s Intellectual Forum. It’s currently designed as an immersive weekend program / bootcamp that uses a “behaviourally informed convening & ideas generation methodology” to tackle some of the biggest challenges facing us. This video and brochure provides an overview of the program.

The next program in November will bring together a group of executives and government officials from the likes of NHS, US Department of Energy, the UN and major corporations, who will each bring a unique challenge to work on. The weekend is structured around problem definition on the first day and creating an action plan on the second day. Over time, she sees the program evolving to provide more tailored, customized programs for clients, and opening up their expert network to help with the crucial stage of applying insights that have been developed on the course. Too often with such courses, freshly motivated execs take their insights back into the mothership where they meet the reality of status quo and lose momentum - Bridget’s focused on helping her clients avoid that fate.

Bridget cites the EAST framework as a good starting point for those looking to apply behavior change insights into their practices, and goes into more detail and nuance during her Curiosity Incubator program. As such, I used that model to frame the discussion, describing it and applying anecdotes and insights from Bridget’s experience to flesh it out.

Looking EAST

The ‘EAST’ framework for behaviour change was developed by the Behavioural Insights Team (BIT) - a group that found success as a UK internal government think-do initially and has since spun out. It suggests keeping four lenses in mind when applying behaviour change in either policy or business settings: Making it Easy, Attractive, Social and Timely.

This is a particularly important message to remember for the economists (and big 4 consultancies) still attached to the idea that humans are purely (or primarily) rational economic actors in the classical sense - homo economicus; this has been thoroughly debunked in numerous places. Economic incentives may in fact play a role, but as part of a broader solution.

1. Make it Easy: Defaults, hassle factor and simple messaging

Defaults has been a poster child success story of behavior change, with ‘pensions defaulting’ as one of the most well-known examples. Switching the default pension contributions of employees from ‘Opt In’ to ‘Opt out’ resulted in a massive 29% increase in UK savings practically overnight. Bridget’s mentor designed that initiative and she shared some of the backstory. While it seems obvious in hindsight, default opt-in was actually one of many different approaches tested, and most people assumed that financial inducements - such as employer matching - or generalized “financial education” would be the key to getting people to save more for retirement.

The change worked, according to Bridget, not because “people are lazy” (the wrong takeaway), but because there were obstacles getting in the way of what people would have wanted to do if they had the choice and the ability (which would have probably been to pick an average savings option, and to opt into the plan). People tended not to do this because overwhelm in the processes prevented them; the mountain of information and steps that new hires are presented with when they join a company, rather than a lack of understanding of the importance of saving for retirement, or a lack of intention to do so.

Bridget demonstrates the ‘hassle factor’ and ‘simplify messaging’ with a case about the California ‘food stamps’ program, CalFresh. This had one of the lowest take up rates in the country, which was largely due to a poorly designed website and workflow (for example poor mobile implementation, requiring phone call verification, and requiring homeless people to enter a Zip Code). Code for America analyzed this and found gaping errors, and provided an overlay site to the service (GetCalFresh), cutting an onerous process down to 10 minutes.

2. Make it Attractive: Awareness and designing relevant incentives

People are more likely to respond to things that are attractive, specific and salient, and / or personalized. Sending offenders images of themselves and their cars captured on CCTV cameras, for example, increased payment rates by 20%.

Financial incentives can and do work, but often need to be considered in a larger behavioural context. For example, Bridget notes that many cities are planning to implement congestion charging. What can be seen as a financial calculation or disincentive is much broader. For example, what alternative options do people have, and what trust do they have in new alternatives being built? London has a plethora of public transport options, but regional towns (including Oxford; and Cambridge is considering implementing one) sometimes have very few. And more importantly, getting people to accept the change is going to be easier if you study the total impact including e.g. public health, and how the built environment encourages certain behaviours and discourages others. It may be easier and more attractive for people to sign up to something that speaks to the health of their children, or their identity as someone making the world a better place, than in just economic terms, or ones involving prohibitions.

It’s also worth noting that financial incentives can backfire - as noted when an Israeli day care center introduced fines for parents picking up their kids late. It resulted in a doubling of the number of parents who came late, as the introduction of a financial mechanism moved the issue from one of reputation and social to the realm of economics; providing moral license, as long as you paid.

3. Make it Social: ‘Conform is the norm’, networks and commitments

Speaking of social, in Bridget’s opinion, this can be the category least considered, but often the most effective lever. After all, we’ve been hardwired for millenia to fear being ostracized from our peer groups, left to fend for ourselves; money is a more recent invention. My characterization of ‘conform is the norm’ basically means: let people know that most people are doing the right thing. Bridget shared the story of solar panels - the data shows that the biggest data point which correlates to whether someone will take up solar panels is not about their cost or financial inducements, but how many other people who have already installed them can the homeowner observe in their neighbourhood.

Networks and commitments matter hugely, especially around health. A person’s chance of being obese is higher if a close friend, sibling or spouse is obese (57%, 40% and 37% respectively). Your broader network context matters too. Bridget shared a story about one of the Curiosity Incubator team member’s projects, working closely with the WHO on the role of mobile phones for tackling diabetes in West-Africa, highlighting the power of the patient association in understanding patients' behaviour including the connection to a religious event leading to a higher uptake of the application.

Commitments have also been found to be very effective - many services use commitments to your future self or others (such as family members or a coach) to increase adoption rates.

4. Make it Timely: Right time right place, time discounting, planning

The timing of an intervention matters - if someone has just had life-altering health news for example, they’ll be far more motivated to adopt lifestyle changes than if all is well. Incidentally, that’s why life stages such as getting married, moving or having children carry such high targeted ad rates (the ‘fresh start’ effect). Bridget noted that in her work with wellness services, the key is follow up; interventions can’t just happen once if they are to be effective. Timely interventions over time can help in forming new norms and helping to change people’s view of their identity (“I’m a person who works out” or “I don’t drink soda”). One of the challenges in large scale deployments - a promising area for technology and the raison d’etre of personal fitness trackers - is ensuring that effective personalized follow up happens at scale.

Similarly, people generally prefer immediate rewards and benefits than far off, more abstract paybacks, which are harder to conceptualize, and mean we are bad in general at predicting our own future behaviour accurately.

The last aspect of ‘timely’ is pre-planning a response to future events; for example people who lay out their clothes for the gym and visualize getting up and going to work out when their alarm goes off don’t have to think and convince themselves, when staying in bed is more attractive. Or planning to go for a walk when the post-lunch slump kicks in. Helping people to visualize and plan ways to overcome barriers to action ahead of time has proven to be successful.

A more meta point about timing relates to the intervention itself. When is it being applied in the process of product development? Bridget notes that all too often a call comes to a behavior change team after the product has been designed and is about to be shipped. “Will people buy it..?”, leaving little room for modifying assumptions, processes or products. This idea about how to incorporate behavioural science more throughout organizations is expanded in more detail in this manifesto for applying behavior change, by Mike Hallsworth from BIT.

Final thought: developing a ‘Behavioural Audit’

Bridget noted that one of the most interesting developments she’s working on now is a more forensic approach to understanding the impact of the proposed behavior change. Does it work on the people actually expected to carry it out? This seemingly simple and important question doesn’t often get the attention it deserves. As a response Bridget has developed a ‘Behavioural Audit’. This is a process that goes into the environment where change is expected and asks “How difficult is it to do the thing that you want to see?”. She then builds a heat map / traffic light score - Red / Amber / Green - describing in detail the steps that actually need to be taken to deliver the change we’d like to see.

In my numerous conversations with Bridget over the past months I’ve been struck by the sense that applied behavior change is getting ready for prime time, and there’s tremendous scope and potential for implementing these more nuanced, human-centric approaches to deliver the changes that business owners and policy makers need. Will be watching her progress with interest, and hope to be back in the UK before long to participate in her courses.