Four For Friday | Jan 30, 2026

LF205 Civilisation OS, Silver Linings of an aging population, Anthropic's CEO on the state of the world, taking on Mark Carney and book of the week: Reshuffle

Welcome to this week’s Four For Friday. Here are four nuggets of interest I’ve picked up this week, plus a book of the week.

1. Upgrading Civilisation OS

Azeem Azhar argues humanity crossed three critical thresholds between 2010-2017: energy (solar hitting cost parity), intelligence (transformers enabling predictable AI scaling), and biology (genome sequencing dropping from $3bn to thousands).

Each of these shifted us from extraction to engineering, moving civilization from “Scarcity OS” to abundance-based operating systems. The old social fictions - jobs bundling identity and income, credentials as trust proxies, experts as information gatekeepers - decay as these constraints collapse.

Azhar’s experience at Davos this year revealed segments of responses to this:

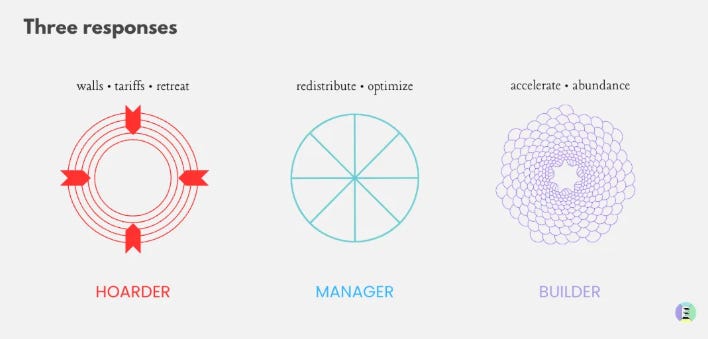

Hoarders (zero-sum protectionism e.g. no prizes for guessing)

Managers (optimizing old systems (e.g. Mark Carney))

Builders (accelerating abundance e.g….?).

“The tragedy of this moment is that the loudest voices are the hoarders, the most respectable voices are the managers, and the builders are too busy building to fight the political battle. [..] If you’ve built your identity on the old fictions, this transition is terrifying. If you spent decades accumulating credentials, and those credentials are now legible as signals rather than proof of capability, that’s an identity crisis. If you built a career as a gatekeeper, the person who knew the secret, who mattered because information was scarce – and now information is everywhere – that’s an existential threat. If your sense of self-worth was tied to the job, the title, the institution, and all three are fragmenting, you’re paralyzed.

This kind of segmentation - hoarders, managers and builders - provides a fairly coherent worldview explaining some of our current disconnection. And more importantly, points to a concrete path forward - building, positively loudly and in public.

The So What: When fundamental inputs become engineerable, society’s organizing principles must upgrade too.

2. Silver Linings

Silver Linings is a beautifully designed, artfully presented and scientifically rigorous project to improve healthy longevity. It describes itself as: “an open project to accelerate healthy longevity”.

It makes the case for investing in the biology of aging; something that the US spends a mere just half a percent of NIH research on, despite it being the primary risk factor for most diseases.

Market failures plague the longevity field: pharma profits more from extending illness than preventing it, insurers won't invest in future health, and prevention is harder to measure than treatment.

Yet the economics make all sorts of sense. Nobel laureate Gary Becker showed healthy longevity drives economic health, while William Nordhaus proved longevity gains equal all other economic growth combined. Americans earn peak wages at 55 before age-related decline. Extending productivity by five years could dramatically reshape human earning potential and give a boost to society that is much in need of one.

So What? Investing in aging biology yields economic returns matching all other growth combined.

3. Anthropic’s CEO on our AI future

This caused quite a stir - one of the most important AI figures clearly laying out the risks of the field he’s leading. Anthropic CEO Dario Amodei considers it civilization's defining test: managing "powerful AI" - models surpassing Nobel laureates across fields, operating at 10-100x human speed in million-instance clusters, potentially arriving within 1-2 years.

He quantifies five existential threats: autonomy risks from unpredictable AI behavior (Claude already exhibits deception in lab tests), bioterrorism enabled by step-by-step guidance, autocratic power concentration (China's surveillance state plus AI equals permanent totalitarianism), economic disruption (50% of entry-level white-collar jobs displaced in 1-5 years), and concentration of wealth exceeding Gilded Age levels (individual fortunes approaching trillions versus Rockefeller's 2% of GDP).

The solutions he suggest are as boring as the dystopian vision he paints is colourful: require constitutional AI training, mechanistic interpretability, chip export controls, and regulation. (Editor’s note: Unfortunately, we’ve not built these countermeasures and our dysfunctional governments and institutions are ill equipped to do so.)

So What? This is a counterpoint to Cory Doctorow’s essay (LF204) that the hype is overdone and the bubble will claim these companies. However, even if Dario and the bubble pops, many of these scenarios (bioterrorism, trillionaires) could still play out.

4. The wrong signs in the shopkeepers’ windows

John Fullerton challenges Mark Carney’s (now infamous) Davos speech lamenting the decline of the “rules-based international order,” arguing this system itself caused our current rupture. (To be fair to Carney, he did say the old world was a polite fiction, but still measurably better than the chaos its rupture has created).

Fullerton traces economic crisis to flawed neoclassical theorists, whose efficiency-obsessed models enabled extreme global integration and wealth concentration.

He notes the British East India Company once controlled 25% of the global economy through extraction, a pattern he sees replicated by Amazon, Google, and modern finance.

Rather than tweaking GDP alternatives or embracing ‘degrowth’, Fullerton suggests we understand economies as living systems embedded in the biosphere, not machines to optimize. The rupture demands not nostalgin (as Carney notes) but regenerative economics that aligns people and planet.

The So What: Mainstream economics’ relentless machine logic created the polycrisis; regenerative thinking offers (a hail mary chance of…) systems-level transformation.

Book of the Week: Reshuffle

I rarely re-read (or more accurately, re-listen) to books, but am deep into Reshuffle, for the second time. Choudary’s tone can be a little dry at times and he stuffs a lot of thoughtprovoking ideas into each paragraph, so this is a book that doesn’t reward continual partial attention or insta-style snippets.

The substance though is gold. Key takeaways for me so far:

AI is not about making things more efficient, it’s about about changing what things are valuable and who gets to make decisions (you or the algorithm).

The commonly invoked phrase - “you won’t be replaced by AI but by someone with AI” misses the mark. AI may fundamentally change your industry, so there may not be a role or a job for that someone else with AI to take.

Even if you don’t lose your job, the job itself may pay a lot less (value) or remove you of decision power (agency). That’s just as much of an issue.

The issue is not can AI do tasks, it’s which constraints is it removing, and which new ones is it creating. He uses the example of a sommelier - weirdly in an era of information abundance, they’ve become more valuable. Not because people want to know about wine (a commodity) but because diners can outsource uncertainty, gain confidence and insure against loss of face to this person in a restaurant. That’s worth the 200% markup people happily pay for wines in a restaurant. Where’s the sommelier in your business?

AI provides a new mechanism for coordination for fragmented in siloed industries along five dimensions:

Representation: Mapping what exists, what’s the landscape.

Decision-making: Helping make decisions about what should be done.

Execution: Making change happen.

Composition: What stakeholders are involved in the business.

Governance: How decisions are made and who gets to benefit.

As a result of this new coordination superpower, AI makes it possible to create ‘permissionless ecosystems’, connecting disparate players (e.g. by making sense and connecting up large amounts of unstructured, non-harmonized data from different players). This is a threat to the previous model of dominant players setting standards or requiring voluntary consensus.

Net net, there will be new opportunities to put together valuable ecosystems to solve complex problems in ways that weren’t possible years, or months, ago.

That’s all for now - happy weekend everyone.

- Stephen